Stunning Māori art in Phantom Billstickers’ frames this summer

Long sunny days – when they finally arrive – are the signal to start spending a lot more time outdoors. So Aotearoa’s biggest street poster company has decided to give people something special to look at when they’re out and about.

From December 2022, you’ll be able to see a selection of inspirational artworks showcased in Phantom’s street poster frames. The company has partnered with Wairau Māori Art Gallery to bring you works from some of the country’s most accomplished contemporary artists.

The featured artworks are Takuahiroa by Kaatarina Kerekere and Navigator by Rangi Kipa. Visually stunning, they are ideal for the poster medium. Yet the meaning of these pieces goes far beyond visual decoration.

Larissa McMillan of Wairau Māori Art Gallery says the poster campaign is a way to express the unique stories of Māori to every passer-by.

“These stories can invoke a sense of curiosity or a sense of belonging and familiarity,” Larissa says. “This campaign says ‘we are proud and present, we are vibrant and intriguing, and we are here with you in your environment. Kia ora.’”

Phantom Billstickers CEO Robin McDonnell says the company is excited to show off such powerful images in its street poster network.

“Phantom’s roots are in the arts sector, promoting events by artists unique to Aotearoa,” says McDonnell. “We couldn’t be happier knowing we’re doing our bit to expose great work to a new audience.”

McDonnell has another tip for Kiwi holidaymakers this summer: Break your road trip in Whangārei, and experience the artworks in their home at the Wairau Māori Art Gallery, which is located in the Hundertwasser Art Centre.

Posters may be fantastic for a first viewing but you’ll appreciate the artworks even more when you see them (and many others) in Aotearoa’s first dedicated public Māori art gallery.

About the artworks and artists

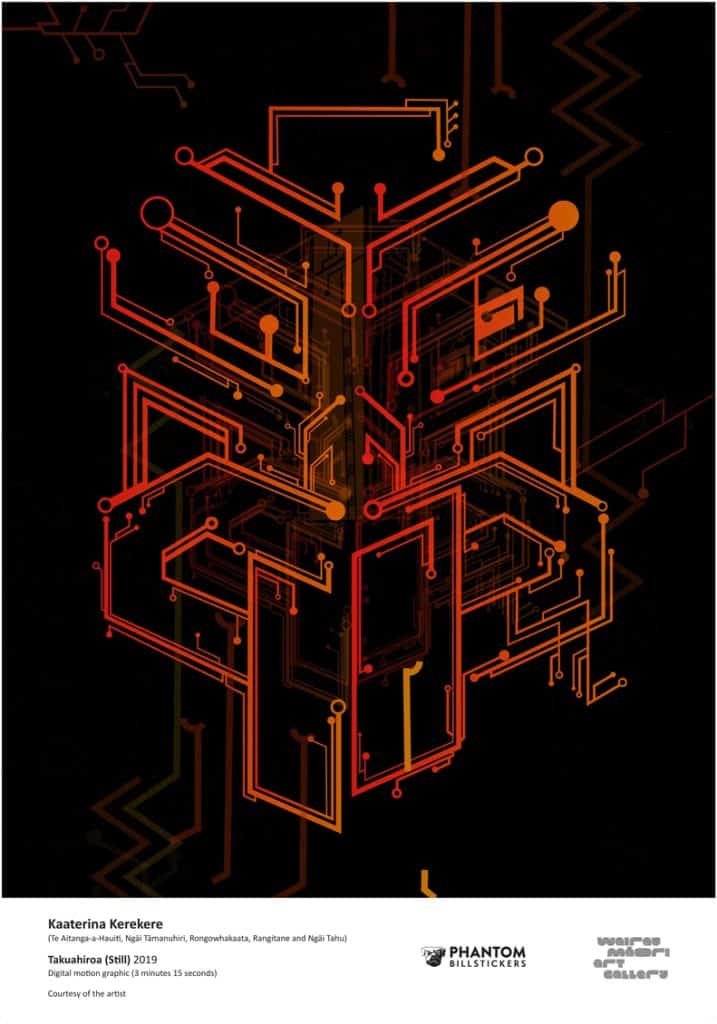

1.

Takuahiroa (still) 2019

digital motion graphic (3 minutes 15 seconds)

Courtesy of the artist

Kaaterina Kerekere

(Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāi Tāmanuhiri, Rongowhakaata, Rangitane and Ngāi Tahu)

Fusing Māori concepts and traditions with a contemporary design aesthetic and digital technology, Kerekere, who is based in Ūawa, Tolaga Bay, has created her visual language to explore themes of whakapapa (genealogy) and mātauranga tāwhito (ancient knowledge).

Using the whare wānanga (house of learning) once located at Takuahiroa, Tolaga Bay as a basis for her research, she has incorporated elements of mōteatea (a lament) alongside graphic motifs to highlight the loss of knowledge in her hapū (subtribe) and iwi (tribe) and to encourage people to stay connected to their papakāinga (homelands) and whānau (family).

“This digital and oral composition combines 378 layers of imagery exploring ideas of space, time, symbolism and intertwined knowledge. It also introduces a new dimension within my work called oro—the echoing and resounding of verse and imagery, connecting oneself and imbuing a

sense of presence.” – Kaaterina Kerekere

2.

Navigator, 2008

solid surface (Staron), colour tinted 2 pot filler

Collection of The Dowse Art Museum, purchased 2009

Rangi Kipa

(Te Ātiawa, Taranaki, Ngāti Tama ki te Tauihu)

This work was the centrepiece of Kipa’s 2008 solo exhibition at Goff + Rosenthal Gallery, New York. It is titled Navigator as it was intended to act as a focal point from which to negotiate the other works in the exhibition. This was one of the few pieces in the exhibition to have the gift of sight, with large, stylised eyes that are always focused on the outward journey and the way ahead.

The work is decorated with celestial maps, which have a dual meaning. They relate to Māori cosmological and ocean-faring histories, and also suggest a more complex pathway for contemporary Māori communities moving from past colonial grievances to a more positive future centred on well-being and growth.

“I think a lot about the need for Māori people to navigate new pathways, to move forward much in the same way that the Māori people originally navigated their way across the Pacific.”– Rangi Kipa

Recent Comments